Investor Psychology: Behavioral Biases That Can Lead to Costly Mistakes

The field of behavioral finance focuses on the emotional and cognitive aspects of investing. In recent decades, well-known economists have advanced the theory that investors' decisions can be driven by human emotions such as greed and fear, which helps explain why asset prices sometimes fluctuate erratically.1

It can be difficult to act rationally when your financial future is at stake, especially when unexpected events upset the markets. But understanding certain aspects of human nature, and your own vulnerabilities, might help you stay levelheaded in the heat of the moment.

Every investment decision should take your financial goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance into account. That's why it's important to slow down and try to consider all relevant factors and possible outcomes.

Here are six behavioral biases, which could also be called mental shortcuts or blind spots, that might lead you to make regrettable portfolio decisions.

- Herd mentality. Many people can be convinced by their peers to follow trends, even if it's not in their own best interests. When investors chase returns and follow the herd into "hot" investments, it can drive up prices to unsustainable levels and create asset bubbles that eventually burst. Joining the crowd and fleeing the stock market after it falls, and/or waiting too long (until prices have already risen) to reinvest, could harm your long-term portfolio returns.

- Availability bias. People tend to base their judgments on information that immediately comes to mind. This could cause you to miscalculate risks or expected returns. In the same way that watching a movie about sharks can make it seem more dangerous to swim in the ocean, a recent news article can shape how you perceive the quality of an investment opportunity.

- Confirmation bias. People also have a tendency to search out and remember information that confirms, rather than challenges, their current beliefs. If you have a good feeling about a certain investment, you may be more likely to ignore critical facts and focus on data that supports your opinion.

- Overconfidence. Some individuals overestimate their skills, knowledge, and ability to predict probable outcomes. When it comes to investing, overconfidence may cause you to trade excessively and/or downplay potential risks.

- Loss aversion. Many investors dislike losses much more than they enjoy gains. Because it actually feels bad to experience a financial loss, you might avoid selling an investment that would realize a loss, even though it might be an appropriate course of action. An intense fear of losing money may even be paralyzing.

Market Moods

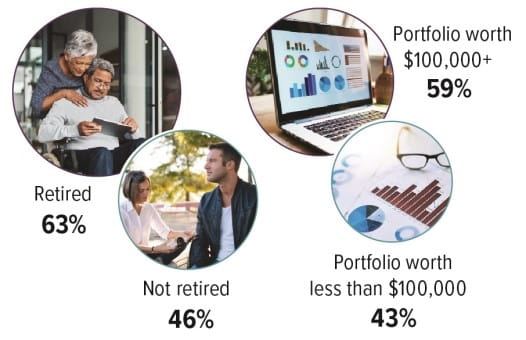

Retirees and higher-net-worth investors were more likely than other groups to say that their daily mood is sensitive to changes in their investment portfolios. The following chart illustrates the percentage of U.S. investors who say the performance of their investments affects their daily mood (a little or a lot).

Source: Gallup, 2019

- Anchoring effect. When making decisions, people often depend heavily on the first information they receive, then adjust from that starting point based on new data. For investors, this translates into placing too much emphasis on an initial value (or purchase price) or on recent market performance. Investors who were "anchored" to the financial crisis may still be fearful of the stock market, even after years of strong returns. Another investor who has only experienced years of gains might be inclined to take on too much risk.

Even the most experienced investors can fall into these psychological traps. Having a long-term perspective and a thoughtfully crafted investing strategy may help you avoid expensive, emotion-driven mistakes. It might also be wise to consult an objective third party, such as a qualified financial professional, who can help you detect any biases that may be clouding your judgment.

All investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal, and there is no guarantee that any investment strategy will be successful. Although there is no assurance that working with a financial professional will improve investment results, a financial professional can provide education, identify strategies, and help you consider options that could have a substantial effect on your long-term financial prospects.

1) "From Efficient Markets Theory to Behavioral Finance," Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2003

Content provided by Forefield for use by Eliot M. Weissberg, CFP®, CFS, of Raymond James Financial Services, Inc., Member FINRA/SIPC. The Investors Center, Inc. is an independent company. The information contained in this report does not purport to be a complete description of the securities, markets, or developments referred to in this material. The information has been obtained from various sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing material is accurate or complete. Any opinions are those of Eliot Weissberg and not necessarily those of RJFS or Raymond James. Expressions of opinion are as of this date and are subject to change without notice.

This information is not intended as a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security referred to herein. Past performances may not be indicative of future results. You should discuss any tax or legal matters with the appropriate professional.